The so-called Marlborough turquoise has been the subject of many identifications, but ten years ago a new identification was put forth by Elizabeth Bartman. In the following article, I would like to discuss the three possible identifications for the male figure. I will also treat the identification of the woman and the history of the gem.

The Marlborough turquoise1[]

|

Fig. 1 The so-called Marlborough turquoise (Museum of Fine Arts of Boston, Henry Lillie Pierce Fund, inventory number 99.109). It is 3.1 cm (1.2 in.) high and 3.8 cm (1.5 in.) wide.a) |

The beautiful turquoise stone, now known as the Marlborough turquoise, belonged until the 18th century to the collection of the Earl of Bessborough. It then became part of the collection of the Duke of Marlborough (from which it derives its name). In 1875 it was sold in one lot with the other Marlborough stones by the 7th duke of Marlborough at Christie's for the sum of £ 10,000 to David Bromilow, who left them to his daughter, Mrs. Jary. She put them up for auction in June 26-29, 1899 at Christie's, where the turquoise was bought together with twenty other stones for $ 16,502.52 by Edward Prioleau Warren for the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston. Since then it has belonged to the collection this museum.

Identifications[]

The Marlborough turquoise depicts a Venus-like woman, by most scholars thought to be Livia although W.H. Gross2 has suggested that it might be Antonia minor, and a male figure. The latter has been the subject of much debate. We can discern two main questions: "Does the figure represents a bust or a child?" and "Who is this male figure?"

Bust or child?[]

|

Fig. 2 Sardonyx of Livia holding a bust of thedeified Augustus (Kunsthistorisches Museum of Vienna, inventory number IX A 95). It is 10 cm (3.9 in.) high. |

The answer to the question whether it's a bust or a living person has been asked by many scholars, because the cameo is unfortunately broken at the bottom. Those who think it's a bust argue that it would not be uncommon to find Livia holding a bust in her hand (Fig. 2). But others argue that the gazing eyes of the figure indicates that it represents a living figure (thought to be a child). However when we look at the physiognomy of this male figure, we notice that it has a mature face and not a child-like face like some scholars seem to think. Therefore I would suggest that it is more likely that the male figure is a bust (it can't be a living male adult because then he would be of the same size as the female figure, which is not the case.3 This will be important in evaluating the different interpretations of the cameo which are based on the identification of the male figure as a bust or child.

Identification of the male figure[]

Until recently there were two main identifications of the male figure, namely Divus Augustus and a "rejuvenated" portrait of Tiberius.4 E. Bartman5 has suggested another possible identification: Drusus maior. I shall discuss each identification and name pros and cons.

Divus Augustus[]

Some scholars6 have argued that Livia is represented as sacerdos divi Augustis holding a bust of the subject of her veneration: her deceased and deified husband Divus Augustus. The subject would then be the same as the cameo in Vienna (Fig. 2). The objection has been made that the male figure looks more like Tiberius than Augustus.7

A "rejuvenated" Tiberius[]

This more widely held identification8 that it represents a "rejuvenated" Tiberius is based on the identification of the figure as a living person in stead of a bust. It is also linked to the story of an extremely white hen with a sprig of laurel in her beak falling unharmed in the lap of Livia who planted the laurel and took care for the hen.9 It has been suggested that Cassius Dio's statement that "Livia was destined to hold in her lap even Caesar's power and to dominate him in everything." (XLVIII 52.4.) refers to Livia's influence over Tiberius.10 But if we don't accept that the male figure is a living person (child or adolescent) then we have to look further for another identification of this figure.

Drusus maior[]

Recently there has been put forward another identification of the male figure by E. Bartman.11 She identifies the figure as a bust of Drusus maior, Livia's deceased son. The arguments of Bartman for identifying the smaller figure as Drusus are the following (p. 83): "In view of his reduced scale, the male must represent either a boy or a statue bust of an adult.73 On the basis of a similar composition in the Vienna cameo (Figure 7912), I suggest the latter as more likely explanation.", "The well-documented portrait iconographies of neither Augustus or Tiberius offer close parallels,74 but the head does recall the few known portraits of Drusus.", "As Rose has documented, Drusus typically wore his hair in heavy bangs parted asymmetrically; they fringed a forehead marked by a horinzontal grease.75 The Boston head renders both of these features in minature; the military costume of the young man, moreover, suits the soldier Drusus.76", "Veiled and wreathed with laurel, the bust evokes the funerary realm.77 Therefore I identify the scene as Livia contemplating a bust of her deceased son."

|

|

|

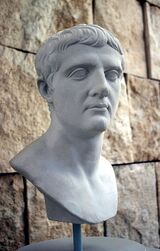

| Figs. 3-5 Divus Augustus (Glyptothek Munich), Tiberius (Ny Carlsberg Glyptothek) and Drusus maior (Ara Pacis Museum = Capitoline Museum). | ||

Conclusion[]

I'm inclined to follow Bartmans interpretation, because it would explain why the figure has Claudian looks and what the underlying message was. I think that this cameo might have had the underlying message that the women of the domus Augusta would have to keep in mind that they could loose a husband, a son or a brother in the public service but that this was an honour for them.13

Notes[]

| a) | Because of the copyright, I can only link to the images to illustrate this article. |

| 1 | I used the following sources for this section: 131743: Kameo der Livia und einer Büste des Augustus, Arachne.uni-koeln.de, C.J.G. DiCamillo, Blenheim Palace Oxfordshire England, DiCamilloCompanion.com, Cameo with Livia holding a bust of Augustus (?), MFA.org. |

| 2 | Review of M.L. Vollenweider, Die Steinschneidekunst und ihre Künstler in spätrepublikanischer und augusteischer Zeit, Baden-Baden, 1966, in GGA 220 (1968), pp. 48-58. Cfr. H. Kyrieleis, Der Kameo Gonzaga, in BJb 171 (1971), p. 173 n. 39. |

| 3 | Of course it is still possible that the male figure was reduced in size to stress the importance of the female figure in relation to him. |

| 4 | If we accept that the male figure is a bust, then it can not be a "rejuvenated" portrait of Tiberius. |

| 5 | Portraits of Livia. Imaging the Imperial Woman in Augustan Rome, Cambridge, 1999, pp. 83-84. |

| 6 | M.L. Vollenweider,Die Steinschneidekunst und ihre Künstler in spätrepublikanischer und augusteischer Zeit, Baden-Baden, 1966, p. 75 n. 62, R. Winkes, Der Kameo Marlborough: Ein Urbild der Livia, inAA97 (1982), p. 137. |

| 7 | Even R. Winkes (Der Kameo Marlborough: Ein Urbild der Livia, in AA 97 (1982), p. 137.) has admitted that « die Gesichtszüge der männlichen Büste auf dem Bostoner Stein mehr denen des Tiberius als denen des Augustus gleichen », but M.L. Vollenweider (Die Steinschneidekunst und ihre Künstler in spätrepublikanischer und augusteischer Zeit, Baden-Baden, 1966, p. 75 n. 62.) has argued that it might be a « tiberianischen Version des Augustusbildnisses, das im Stil dem Tiberius-Porträt angeglichen ist ». |

| 8 | J.M.C. Toynbee, Review of L. Polacco, Il volto di Tiberio: Saggio di critica iconografica, Rome, 1955, in JRS 46 (1956), p. 159, W.-R. Megow, Kameen von Augustus bis Alexander Severus, Berlin, 1987, pp. 256-257 nr. B 19, M.B. Flory, The Symbolism of Laurel in Cameo Portraits of Livia, in MAAR 40 (1995), pp. 52-53, 60-61, S.E. Wood, Imperial Women: a Study in public Image, Leiden, 1999, pp. 119-121 (more nuanced). |

| 9 | Plinius maior, Historia Naturalis XV 136-137, Suetonius, Vita Galbae1, Cassius Dio, XLVIII 52.3-4. |

| 10 | As noted in S.E. Wood, Imperial Women: a Study in public Image, Leiden, 1999, pp. 120-121. |

| 11 | Portraits of Livia. Imaging the Imperial Woman in Augustan Rome, Cambridge, 1999, pp. 83-84. |

| 12 | This is our Fig. 2. |

| 13 | It might even have been carve for Antonia minor to consolidate her with the loss of her son Germanicus and to remind her how Livia had carried her grieve over the loss of her son (and Antonia's husband) Drusus. |